An obscure, remote setting. An enigmatic structure. A Lost Place.

Walking through the bunkers on the beach evokes an eerie feeling in the stomach. Graffiti adorn the cement walls. The low waves of the Baltic Sea relentlessly thump against the steel and stone frames. In the forest, you stumble across railroad tracks and red brick walls overgrown with grass and moss. Few people enjoy the peculiar scenery.

We are in Karosta, just a few miles north of the Baltic sea port of Liepaja, Latvia.

Latvia has seen many invaders and occupiers come and go during the past centuries. Its strategic location on the Baltic Coast turned it into prime real estate for Knights, Swedes, Poles and Russians. German settlers from the Livonian Order had established their authority on the shore. The Duchy of Courland experienced a brief glorious period, even acquiring colonies in the Caribbean and Africa. The Russian Empire took control of the coastline after defeating the Swedes in 1721, without touching the German-speaking Lutheran elite’s social, economic and religious privileges.

Peter I built his new capital St Petersburg in the marshland of the Neva estuary. The Baltic lands promised a new window to the west. The Emperor was a shipbuilder, and his keen eye for ports and naval facilities fell on a small island in the Finnish Sea. Rechristened Kronshtadt and equipped with a remarkable fortress, the island was the headquarters of the Russian Baltic Fleet for several centuries. But even Kronshtadt’s waters froze in the harsh Northern winters. Peter’s Baltic Fleet desperately needed ice-free harbors.

A few hundred miles down the coast, the small town of Libau (Liepaja/Libava) was the Duchy of Courland’s main export harbor. Now under Russian control, Libau, mostly settled by Germans, grew in significance. From here, a steamboat service connected Russia with New York. For many persecuted Russian Jews, Libau was the point of departure on their way to the United States or Canada. The first Transatlantic telegraph cable tied Russia to the world. Libau was also the Russian Empire’s westernmost port, and soon turned into the summer home for the Imperial Navy’s Baltic Fleet. Its population grew from 10,000 in 1863 to 84,000 in 1911.

In the age of steam and dreadnoughts, Libau/Libava captured the imperial imagination. The only drawback was its close proximity to Germany, only 70 km to the south.

Alexander III plans a new naval port in the Baltic

In the late 19th century, a fresh initiative pushed the dreamy backwater into the foreground of imperial ambition. Turning away from the traditional Prussian alliance, Tsar Alexander III listened to French overtures. Loans from Parisian banks allowed the Empire a large-scale armaments program including railroads, barracks, ports and battleships. Reeling from defeat against Prussia in 1870-71, France urged Russia to spend more money fortifying its precarious Western border. This was where the Russian ‘steamroller’ was supposed to jump off to destroy the Hunnish hordes, in the ultra-nationalist language of the day.

Known as ‘the bullock’ because of his physical strength, Alexander III prepared for a possible war with Imperial Germany. Authorized by his imperial seal, the Russian Treasury spent millions of rubles to finance projects on the Western border. Naval construction fit the bill. In 1890, Alexander III gave the green light for an ambitious naval construction project: the building of a grand new military harbor. The Admiralty designated Libava on the Baltic Sea as a major link of the defensive ribbon around the Empire. Engineers and workers built breakwaters, canals, gunnery batteries and a wide range of barracks and auxiliary buildings. Naval engineers soon designed a long canal to allow the fleet to seek shelter. Around the port, a massive modern fortress arose. Redoubts, casemates and passageways were built in a state-of-the-art stronghold, with a ring around the port to protect it from attacking ground forces. Artillery stationed on floating platforms on a nearby lake guarded against a potential surprise amphibious attack. The Northern forts followed the designs of similar naval bastions such as the one in Port Arthur (now Dalian).

Kara-osta: Karosta (War Port) emerges

Detailed blueprints outlined the ‘Libavskii Voennyj Port’, a veritable Russian outpost: Housing for officers and their families, conference quarters, watch-towers, exercise spaces, and a large onion-domed church: the St Nicholas Maritime Cathedral. Offering space for more 1,500 worshippers, the Cathedral was built in the old Muscovite style, symbolizing the revival of medieval shapes and forms. For other buildings, metropolitan architects borrowed liberally from the styles of the turn of the century: art nouveau, historicism, national romanticism. Latvians called the place Kara-osta (military port) or Karosta. It became an eclectic mix: a small Russia away from home for sailors and officers and their families.

The best surveyors came from St Petersburg to turn Libava into a modern naval port. Special dredges made in Marseille cut the canal deep enough for the battleships. Plans allowed for the entire Baltic Fleet of 50 ships to find refuge inside the port. A few years later, the first Russian submarines would ply the waters off the port. Two long breakwater walls protected the harbor from storms. They are still visible today. Somewhere in one of the cement blocks is a time capsule from 1894 containing gold coins and the Tsar’s personal standard. Characteristically, the ‘bullock’ named the harbor after himself ‘Port of Alexander III.’.

A blue cross on a white background – the St Andrew’s flag of the Imperial Navy flew over the bold project. Within a few years, Russia had constructed a fresh ‘window to the West’. It bore testimony to the rapid industrialization between 1890 and 1913, the era of Russia ‘catching up’ to the other modern industrial nations. The naval port at Libava, finished in 1906, symbolized the growing pride of the Russian Navy.

Demolition begins in 1908

But only two years after work had subsided, Nicholas II ordered demolition crews to begin blowing up parts of the fortifications again. Cannons were moved to other locations or melted down. Since that time, several bunker structures have been ‘melting’ into the beach. Why did the Emperor reverse course? Was he convinced that the maintenance of the fortress was too costly? Did he want to appease his German relative, the Kaiser? No one knows for sure.

Kolchak Commands the Sea

Libava’s most prominent commander was Alexander V. Kolchak. As a boy, Alexander had always wanted to be a naval officer, joining the navy cadets at an early age. Kolchak served in the Russo-Japanese War and spent several months as a Japanese Prisoner of War. Reaching the rank of Admiral, Kolchak served in Libava/Libau from 1909 to 1912. Kolchak might also have seen the ‘Akula’, one of the first Russian submarines in 1912. His headquarters, today known as ‘Kolchak’s House’, allowed the senior officers to follow the ships’ movements in the port and signal orders from the roof.

The viewing area on the roof is more than 3,000 square meters. It is easy to imagine naval officers in their summer whites looking through binoculars and signaling turns and twists to their cruisers, frigates and battleships.

Running the Navy’s western outpost was prestigious and came with social responsibilities. Gala dinners and receptions drew the local and regional elite as well as courtiers from St Petersburg: Proud Russian officers in uniforms full of ribbons and medals and ladies in the latest French fashions dancing in the long white nights of Northern Europe.

Paintings shipped by ship…

Money was not an issue for the Imperial Administration. Estimates for the total cost of the Naval Port construction range from 45 to 83 million gold rubles. Facades were modeled after the edifices of the Imperial Capital and carried glorious heraldry motifs. Crimean marble adorned the staircases and halls. A small park reminded visitors of Versailles but more importantly, the Russian copy of it in Peterhof. Large paintings of Alexander III and later Nicholas II were commissioned for thousands of rubles. They had to be literally shipped to Libava since they were too large to fit into a train carriage.

Alexander’s son Nicholas continued to shower favors on Libava/Libau. The Royal yachts were berthed here, ready to provide the court with a delightful outing in the calm Baltic waters. In 1901 and 1903, Tsar Nicholas II visited Libava on his inspection tours of the Baltic Fleet. These summer visits were a grand affair. Nicholas took his entire family. Pictures show his daughters strolling around the ships in their finest dresses. From Libava, the unfortunate Nicholas may have spent happy days sailing the sea on his yachts ‘The Standard’ and ‘The Polaris’.

Homing pigeons for a ruble

Maybe the most unusual legacy was the special station for homing pigeons. Eight staff members took care of the messengers, with exactly 1.29 rubles per pigeon ear-marked in the naval budget. In training exercises, the birds impressed everyone. In 1907, 90% of the pigeons shipped to Copenhagen and released there found their way back to Libava – a distance of over 700 km (430 miles).

It was in the magnificent St Nicholas Maritime Church that prayers were said in 1904, when the ill-fated Baltic Fleet stopped by en route to Japan. Libava was the last Russian port on their journey to defeat at Tsushima.

The shock waves of this humiliating defeat reached the shores of Libava quickly. Sailors mutinied against the Tsar’s commands. Just like in other garrisons and fortresses across Russia, soldiers and sailors refused orders to fight. In June 1905, about 4,000 sailors rebelled. The authorities regained control, and 8 of the rebels were shot. Many others were exiled or demoted.

German occupation

In the end, the fortress did not serve its primary purpose: to stop the advancing German army. When the First World War broke out, the port was evacuated. The chandeliers, the contents of the wine cellar and other precious goods were brought to safety. German troops turned the headquarters into a war hospital and recreation space for officers.

The fortress was far away from the turbulent events of the February and October Revolutions in Petrograd. Some of the batteries then saw a bit of action when Latvia declared its independence and White Russian and German militias, the so-called Bermont troops, tried to take over in November 1919. The former Commandant Kolchak, an ardent foe of the Bolsheviks, led the White Armies against Lenin and Trotsky. But he was unsuccessful and eventually captured and executed by the Bolsheviks.

The new independent Latvian state had difficulty making sense of the huge military infrastructure it had inherited from the now-defunct Russian Empire. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Latvian army stationed several infantry regiments on the territory of the former port. The Red Cross converted some buildings into a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients.

Soviet takeover

Then, the Russians came back. As a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Latvia was taken over by the USSR. The Red Navy smoothly settled in where its Imperial predecessors had left off twenty years ago. Red sailors now recuperated in the Naval Hospital and relaxed in the spacious gardens. The Soviet 67th riflemen’s division took up in the old barracks. The entire port facility was sealed off hermetically, and even inhabitants of Liepaja could not enter the military zone without special permission. Karosta now was a Soviet military base in the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Only one building did not see a return to the heydays. St Nicholas Maritime Church became a movie theater. The Red Navy bricked up the central cupola bricked up to improve the movie sound. A ‘red corner’ listed exemplary servicemen and commemorated Soviet festivals and anniversaries.

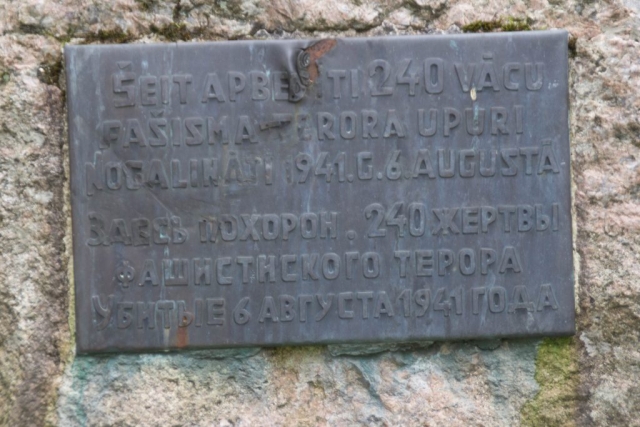

Soon after, Karosta again changed hands. When Nazi Germany invaded the USSR in 1941, the fortress offered a heroic but short-lived defense. Five days were enough for the Germans to capture the stronghold. The Nazis used the guardhouse for the court-martial cases against deserters and suspected spies. The nearby burial ground contains about 90 victims. (No effort was made during Soviet times to commemorate these victims. The tourist brochure simply states that ‘the place was evened’ in 1957. Instead, the Soviets built a football pitch for the sailors).

Cold War in Karosta

When the Soviets returned victoriously in 1944, Karosta returned to be a Soviet outpost in the Baltic. During the Allied negotiations, Stalin made the argument that the Soviet Union deserved an ice-free port in the Baltic – and received the Prussian city of Königsberg (today Kaliningrad). Neither Churchill nor Roosevelt or Truman were aware that Libava/Libau already offered this opportunity for Stalin. Moscow could argue that Liepaja ‘returned’ into the fold of the Mother country as the city had been part of the Russian Empire since the time of Peter the Great.

In the soon developing Cold War, Karosta resumed its significance as a major naval port and became a missile proving ground for the Soviet Navy. Soviet officials saw Liepaja not only as an asset but also as a potential liability. The Iron Curtain had to be without loopholes. Latvians with ties abroad had to be checked carefully. Many were exiled. Fishing trips had to be restricted. The beach was also monitored for signs of foreign agents landing ashore. After 9 pm, a curfew prevented anyone to step on the beach. Karosta, an area of about a third of the city’s territory, was off limits to the local population. Soviet maps did not show the base.

The garrison numbered between 20,000 and 25,000 sailors. 30 nuclear submarines and more than 100 naval vessels called the port home. In-migration from other parts of the USSR meant that Liepaja had a majority Russian-speaking population by 1979.

Dark Tourism and Brutalist Soviet Relics

But with the end of the Cold War, the Soviet Navy had to leave independent Latvia. In 1994, the area was returned to the Latvian administration, and today, about 8,000 people live here. Karosta ceased to be sealed off. Housing conditions are poor: Soviet apartment blocks are not known for aesthetic or practical comfort. Still, St Nicholas Maritime Cathedral has been restored and its shiny golden domes are the perfect motif for plein air painters. A sign warns visitors not to enter the Cathedral with evil thoughts.

Karosta is what remains of the prestigious Imperial ‘Libavskii Voennyj Port’. It provides a rare opportunity to visit the legacy of the Russian Empire within the boundaries of the European Union. Karosta is one of the most intriguing ‘memory spaces’. Massive concrete blocks shift in the sand and threaten to collapse at any moment. Munitions supply tunnels dot the landscape. Water seeps through the cracks and creates eerie stalactites in the dark bunkers. Young men gather here to spray-paint the walls or conduct shady deals. On Sundays, tourists come to contemplate the ‘fortress falling into the sea’. The ancient protective architecture has become a spot on the Baltic tourist trail.

Now, fortress aficionados tour the grounds, with the detailed guidebooks of their passion tucked under their arm. Dark tourism flourishes as visitors can book to stay a night in the guardhouse, under the watchful eyes of ‘Soviet’ officers. For several years, artists found refuge in some of the abandoned buildings.

Just like other monuments, Karosta’s journey shows that the past is never truly forgotten. Society keeps interacting with history – sometimes a site is vandalized, sometimes it is adapted. The remains of history can be neglected and sink into oblivion, or they can be renegotiated and re-visualized as something entirely different. Karosta’s future is unknown, but the traces of its fascinating history are clearly visible. Today, the ruins of Karosta are a stark reminder of the enormous resources spent on military hardware before the First World War. They offer an insight into forgotten places.

Additional detailed information contained in the brochure ‘Karosta’, written by Gunars Silakaktins.