Ironically, Adolf Hitler was not interested in the Olympic movement. He was not into spectator sports, since he liked to be the one in the spotlight. For the Nazi ideologue, watching athletes competing peacefully across international boundaries seemed ridiculous in the age of struggle and social darwinism. In 1931, the International Olympic Committee award the 1936 games to Berlin. Work started on the stadiums and athletes’ quarters. Eventually, the Nazi government understood the potential of hosting the famous event. The propaganda opportunity was not to be missed, so the Berlin Olympics in 1936 turned into a global show of Nazi values. The venues erected for this occasion still stand, as do the statues around them. Thousands pass them by without paying much attention. Is that a good thing? Should they be removed and placed into a museum, finally?

Since 1945, the Allies (who ran West Berlin) and subsequently the German authorities have debated what to do with the architectural legacy. Just like many years before, contemporary critics demand the “de-Nazification” of the area around the Berlin Olympic stadium. It is embarassing and intolerable, they argue, to allow the Nazi art to remain in its place, as if the world had not seen the terrible effects of racism and Nazi crimes. The critics have a point: It is at first a shock to see the unrepentant glance of these monuments. You are looking straight into the abyss of Nazi ideas. For example, Karl Albiker’s “Discus throwers” and the “Relay racers” , located on the south-eastern edge of the Olympic field. The statues display the Nazi cult of the body: Impersonal athletes, allegedly of pure blood (or stone). They invoke the classical age: Rome and Greece are again abused for imperial gain.

There are a number of these kind of statues around the park: Arno Breker, for some Hitler’s favorite artist, is also represented with two statues depicting a decathlete and a female “winner”. Many have in the past called for the removal of these sculptures. Yet, they are still standing. Possibly, the reason is the complex creation story of the park: Designed by the brothers Werner and Walter March, the area had been in the planning since 1926, when Werner had won a competition to build a sports arena. But delays occurred, and Werner emigrated to the United States, where he worked with Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius. In 1932, another chance opened up, and Werner returned as a U.S. citizen, immediately recruiting his younger brother for the team. Both felt the Olympic movement deserved a close modeling of ancient Greek and Roman venues. The plan lists “stadion” (stadium), “forum” (assembly area), “templon” (hall with sacred items), “theatron” (event venue), “gymnasium” (academy), and “palestra” (public gym). Art critics and the German Olympic organization are in favor of letting the statues stand. They claim they represent the vision of the March brothers, and not the Nazi ideology.

The former “Reichssportfeld” is a challenging place. Visitors can still visit the Langemarck Hall with the inscriptions glorifying the senseless death of young volunteers running to their death in November 1914 in Flanders. Not many places in Germany depict unreconstructed Nazi myths. Maybe that is why this is helpful to preserve, so not all sites are “sanitized”. Elsewhere, postwar iconoclasm has removed Nazi eagles from official buildings, and only careful city guides can point to urban legacies of the Nazi period.

Since 1945, the debates have waxed and waned, especially since the German government took control of the territory from the Allied (British) forces. Big events have taken place here: athletic meets, world cup finals, football matches. Every year in May the German Football Association, the DFB, stages the national cup final in the Berlin Olympic stadium. Another layer of memories has been placed on top of the earliest narratives. Spectators have walked past the Nazi statues, not even pausing in their stride to the big match. Few stop to approach them and study them carefully. Fewer even start to debate why they are here. They have been “historicized”, of interest mainly to academic art historians. They no longer matter. Or do they?

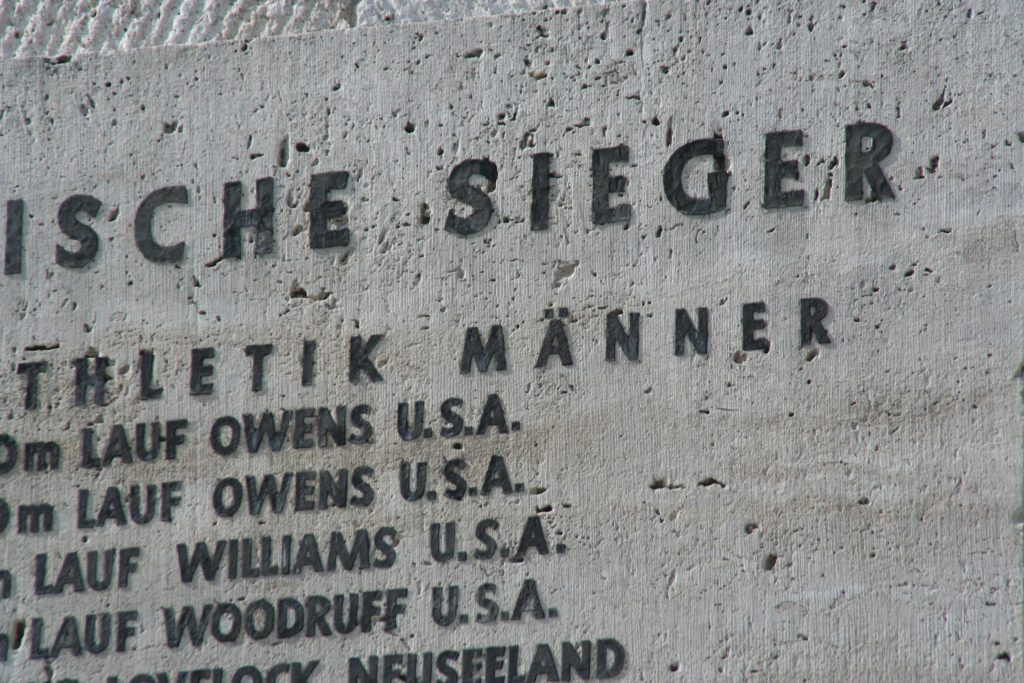

Adolf Hitler was disappointed by Jesse Owens’ famous victories, undermining the Nazi racial fantasies. Even though the statues remain, the Olympic venue in Berlin is decidedly NOT a contemporary celebration of Nazi ideology. It is more: a place of memory, good and bad, conflicted and glorious. One sculpture even reminds us of a delicate irony: The “relaxing athlete” by Georg Kolbe seems to reflect the athletic ideals of a muscular “Aryan” man. Indeed the sculptor Kolbe had used the German-Jewish musician Hans Loewy as a model. Ironically, the Nazi “golden pheasants” marched past a proud German -Jewish man on their way to watch Jesse Owens win.

In compiling this post, I would like to express my gratitude to Volker Kluge of the DOG who published an article here https://olympischesfeuer-dog.de/2020/08/31/aufgewaermt-ja-heuchlerisch-der-skulpturenstreit/.