This is the center of Germany. Smack in the middle. Along the divide. If you want a taste of what the Cold War looked like, go no further. U.S. troops and Soviets faced one another on a daily basis: Monitoring communications and watching each other’s every movement through binoculars. Today’s peaceful landscape is misleading. At Point Alpha, we are at one of the hot spots of the biggest military confrontation the world has ever seen. Two social systems. Two ideologies. Two massive war machines ready to spring into action at any moment. No compromise.

Germans have united their country. Over the last thirty years, some of it has grown together. Other parts have drifted apart again. Although society continues to stitch together the two divided entities, there are cracks and seams. This is one of the historic seams. The former border between the Federal Republic and the German Democratic Republic crossed right over this terrain of wheat fields, gentle hills, and forests.

There are no massive peaks or majestic lakes here in the triangle between the states of Hesse, Bavaria and Thuringia. You are exploring what the Germans call “Mittelgebirge”, a medium range of peaks known for its chilly winters and bare summits. The common name is the “Rhön”, a word derived from the Celtic “rann” (mountain) or the ancient Nordic “hraun” (stony land).

It was and is a harsh environment, with freezing temperatures in winter and cool summers. In medieval times, robbers threatened the traveler, and several legends recall Robin Hood-like bandits. Throughout most of its existence, this region was on the periphery of history. The soil does not contain any important natural resources. No significant roads or waterways connect the area with major nodes of trade. Few Germans outside of the area would be able to pinpoint on a map where the Rhön is. Some may have heard of its highest peak, the Wasserkuppe summit: It is the center of German gliding activities, and tourists can book a short flight to get a sense of what birds see. The German heartland is far away from the Romantic Road or the castles along the Rhine.

As you drive through the hills and glens, you come across signs proclaiming that here, on a particular day in 1990, the division of Germany ended. These markers indicate when the border between East and West was opened at this location. They serve as a reminder for current and future generations in a time when the differences have been paved over for the most part. At first glance, you cannot ascertain whether you are in the former East or the former West Germany. Only very careful observation will reveal still existing economic differences: Fields are larger in the East, since land reform expropriated the large estates and state farms took over in the 1950s. In Thuringia, there are many villages without a single store, where itinerant trucks sell bread, sausages and vegetables to the mostly elderly still living here. The young and enterprising have moved or commute to nearby towns and cities.

For military historians, this is the core area of the Fulda Gap, an area of few natural obstacles for an invading army. Seen as the logical invasion route for Warsaw Pact troops, the Gap became a staple of Cold War planning and popular culture (There is even a board game). Frankfurt, the hub of German industry and banking and the home of U.S. military headquarters, is only 90 km away. The Soviet army distributed its forces across East Germany. As a precaution, NATO dotted the landscape with bases and barracks. The Fulda Gap needed to be plugged to prevent a Red wave engulfing Western Europe. Along the Eastern side, the Communist regime moved people around like pawns in a chess game. East Berlin created a no-man’s land dedicated to border security. On the Western side, there was no such government intervention. Of course, the economy suffered. Commercial routes were cut off suddenly. But the impact was manageable, except for the heavy military presence. NATO tanks tore up the soil during maneuvers, and German taxpayers compensated the villagers for any damage. In many areas, the natural environment was off limits. Summits were cordoned off for hikers and the militaries of each side transformed large stretches of land into camps and massive training territories.

The border line itself was the result of Allied agreements in 1945. By the end of the Second World War, U.S. troops had marched deep into Thuringia and even installed mayors in many towns. The spot where the Allied militaries met -Torgau on the Elbe river – lies deep in Mitteldeutschland, close to Berlin. But the Big Three -Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin- had compromised on the state line of Thuringia and Hesse as the border between their respective zones of occupation, and the U.S. Army withdrew again. At that time, it looked as if this relocation would have little consequence. Surely, the Allies would agree on a joint policy regarding Germany soon. But with tensions rising and the Cold War getting uglier in 1947, the strictly administrative line soon became the border between two hostile systems. When two German states were established in 1949, this line marked the border of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), buttressed by hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops. But it also marked the dividing line between democracy and Communism – the “Iron Curtain”.

To keep the border secure, the GDR government completely changed the structure of the rural society. Farms close to the barbed wire were destroyed and the inhabitants and their livestock relocated. A border regime regulated who could enter the exclusion zone. Anyone suspected of harboring anti-Communist views had to face arrest and deportation. Along the fence, the guards developed a perfect system to prevent any GDR citizen from escaping. Watchtowers allowed for a direct view of the nearby fields and hills. Any enterprising person attempting to flee the country would have to make his or her way through an obstacle course of fences and minefields. In case anyone attempted to “flee the Republic” – the official designation – searchlights alerted the garrison. Guards would drive their Trabant patrol cars on a special track to catch the culprit. By that time, a self-triggering spring gun might have already killed the unlucky escapee. Officially, of course, the security was needed in case of a surprise NATO attack on the “peace-loving” GDR.

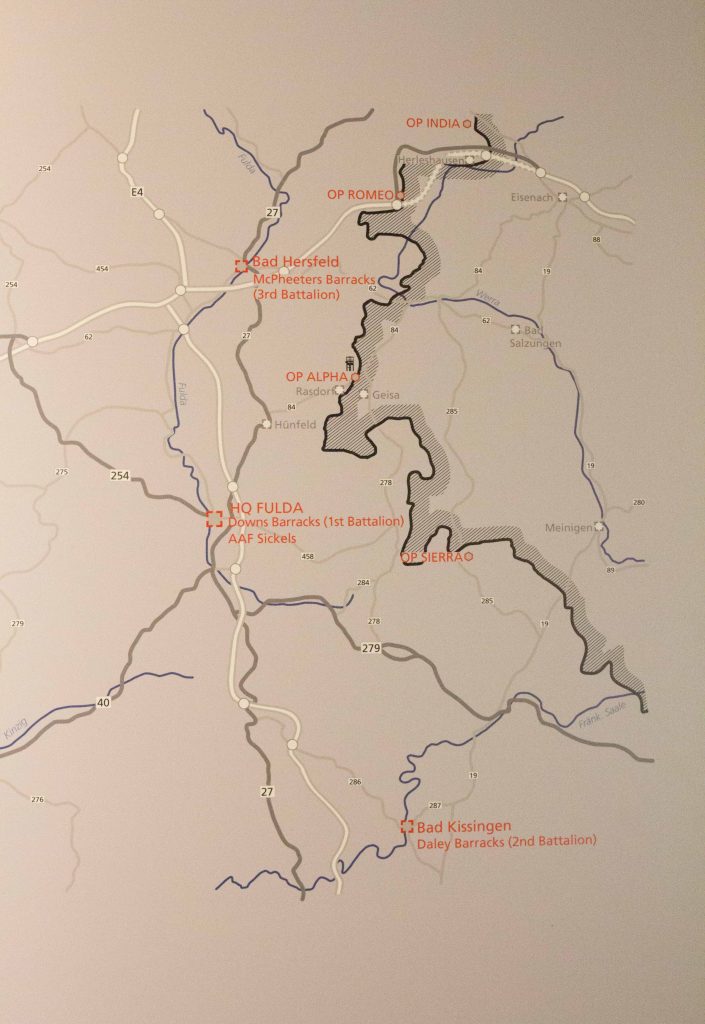

Faced with the “Iron Curtain” and an expansionist Communist threat, the West could not afford to be left in the dark. In addition to sending spies across the divide, the United States and its Allies established a network of monitoring stations to listen in on Warsaw Pact movements. Several high-tech radar facilities on the Wasserkuppe summit at an elevation of 900 meters attempted to capture Communist communications deep inside the GDR. On the border, the West needed another puzzle piece. Observation Point (OP) Alpha was established as the first of several forward observation posts, situated on an elevation of 411 meters. Afterwards, OP Romeo, OP Oscar and OP India were built. In 1972, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment “Blackhorse” took over. One platoon of armored cavalry was stationed here, with ten vehicles. About forty men were deployed here in regular times, up to 200 could be on duty in times of crisis.

This spot right on the border was not intended to be a combat position. But it was needed to get a sense of what the Warsaw Pact was planning. Point Alpha was part of the advance warning system. In 1985, a new concrete tower was built which is still standing. From here, the soldiers could observe activities on the other side of the divide. The AN/PPS-5 ground surveillance radar allowed the U.S. army to detect a tank from 10 km away. Should the Reds invade, the men and women stationed here would observe some preparations and raise the alarm. In case of invasion, they would quickly retreat. Or so it was planned.

The Fulda Gap was the site of potential nuclear warfare. Faced with an overwhelming conventional force, NATO reserved the right to answer an attack with tactical nuclear bombs, some as small as a large suitcase. The bucolic scenery would have been transformed into a post-Armageddon moonscape. Fortunately, it never came to this kind of escalation. The doctrine of deterrence worked.

With the Cold War over, the landscape has recovered, and it is all peaceful here. Military listening stations and observation posts have been dismantled or have become museums. In 1991, the U.S. gave up Point Alpha. After housing asylum seekers, the future of the installations seemed bleak. The local government planned to raze the buildings and let nature reconquer the site. Fortunately, a protest movement prevented the destruction. Concerned citizens wanted to preserve the memory of divided Germany.

Instead of getting demolished, the buildings continue to serve a critical function. The Point Alpha foundation oversees a large complex with fascinating artefacts, inviting schoolchildren and history buffs to ponder the Cold War era. The museum displays the Warsaw Pact invasion plan right through the Fulda Gap, last updated in September 1989.

Regularly, the German government invites American teachers to tour the area for some first-hand experience of the Cold War confrontation in Europe. It is part of the Transatlantic Outreach Program (TOP). West Point graduates also visit to get a glimpse of Point Alpha’s significance in history. Once a year, the U.S. flag is exchanged in a special ceremony.

The casual observer can become a Wanderer between the worlds, consuming a hamburger on the former U.S. camp in the aptly named Black Horse Inn or taste a Russian-legacy solyanka soup in the former East German city of Meiningen. You can visit Point Alpha or its less impressive Soviet counterpart Hohe Geba on the Thuringian side. A mesmerizing mural inside the Black Horse Inn depicts Soviet and U.S. soldiers on patrol carefully watching each other in the snowy landscape.

Memory locations have sprung up like mushrooms to remind the young of the fissures of the past. Art installations commemorate the hardships of a divided country. The former death strip has morphed into a huge Green Belt of nature preserves. Because it was off limits during the conflict, several endangered animals and plants have survived here, and now they enjoy protection. This is true for other parts of the Rhön as well, which is now an official UNESCO biosphere preserve. Several elevated moors such as the Red or the Black moor are famous as nature destinations and sanctuaries for very rare species.

Sheep are common as the Rhön’s signature animal. Like elsewhere, they are not raised to produce wool or meat. Their wool is too scratchy for cashmere-spoiled customers. Lamb is uncommon on German tables. Besides, it is not worth competing with agro-industrial corporations. Instead, they are keeping the heath landscape from overgrowing and the forest from covering the hillsides. Count yourself lucky if you stumble upon a flock guarded by smart sheep dogs.

Currently, the Rhön is a hiker’s paradise: easy-to-moderate hikes of all lengths, plenty of castle ruins, and quaint village inns to quench your thirst. It is off the beaten track, unlike Point Alpha during the Cold War.