Like many cities in Germany, Cologne suffered major destruction during the Second World War. It was the target of the first attack with more than a thousand bombers. Allied air raids turned more than 80% of the city center into a wasteland of rubble. The area around the famous Cathedral became a symbol of the price to pay for the Nazi dictatorship. Today, postwar reconstruction and decades of prosperity have almost removed the traces of annihilation. Sure, gap-toothed buildings remind the careful observer of bomb hits that were merely patched up. German bomb removal squads still defuse a bomb per week when construction crews notice a certain dangerous shape. But the average tourist will have trouble discerning the traces of war. For sixty years, the cathedral sported a bricked-up part where bombs had hit the magnificent church. It was meant to be a reminder of war. Recently, the makeshift filling replaced by fresh stonework, removing the scars of war. Long overdue or a worrying symbol of a desire to forget?

Drawing A Line Under The Past?

As is common in Germany, there are multiple voices. The recent electoral success of the AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) has brought voices into the public that demand an end to the ‘German guilt’ debates. They describe as ‘self-flagellation’ what the majority still believes is a necessary cathartic process. Most people are shocked by what is now being said in public. Is it really time to draw a line under the Nazi past? Maybe it is helpful to remember the process in which Germany addressed the Nazi legacy.

Dealing with the past has a long history in postwar West Germany. Journalists coined the term Vergangenheitsbewältigung to express society’s efforts to ‘come to terms’ the dark days of the Nazis. In Cologne, the Nazi Documentation Center (NS-Dokumentations-zentrum) has long played a pioneering role in demanding transparency and discussion. It was an effort ‘from below’ as the city council only reluctantly recognized the need to face its brown chapter. Local activists contacted Jewish survivors and invited them to visit their home town. They also reached out to former slave laborers in Poland and the USSR.

Trying to piece together a comprehensive picture of the city that was lost was a complicated and arduous process. Using the guidebook for ‘Jewish Cologne’ is a walk down memory lane, with many surprises along the way. With the help of many dedicated associates, Barbara Becker-Jákli collected the documents and images that provide a fascinating glimpse into centuries of Jewish life in Cologne, including the Nazi-era destruction of the community and its continued existence today. (Barbara Becker-Jákli, Jüdisches Köln. Geschichte und Gegenwart. Ein Stadtführer. Emons Verlag 2012.)

Stumbling Stones

Visitors will likely ‘stumble’ upon memory stones placed in front of houses. The Cologne artist Günther Demnig has long been active commemorating the Nazi crimes in a creative fashion. He painted the path that Roma and Sinti had to take through the city on their way to deportation. Then, he started to place brass cobblestones with the name and death dates of Jewish individuals in front of their last recorded place of residence. Throughout the city, and indeed, throughout many cities in Europe, these shiny brass ‘stumbling stones’ arrest the wandering tourist and force him or her to remember that the Holocaust happened right here, not in some far away camp.

In this way, visitors recognize the vibrant Jewish life in Germany’s fourth-largest city.

According to historians, Jews settled in Cologne as far back as the fourth century AD. In 321, Emperor Constantine allowed city councils to nominate Jews. At the time, this was not seen as a privilege as public office came with onerous costs for representation. Cologne’s Jews were well organized and wealthy, and the Christian councilors resented that their fellow patricians were exempt from these expenses.

Medieval Cologne

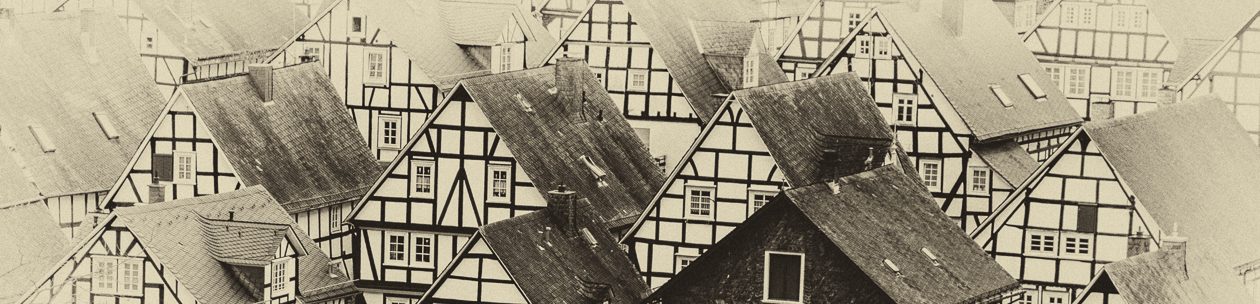

In medieval times, Cologne was Germany’s largest city and the most important trade center. Guilds ruled the day. Artisans occupied small alleys named after their specific craft. Not all trades were male-dominated – one street was reserved for female silk traders. The streets along the Rhine river teemed with warehouses. Cranes moved cargo from the barges. One sector of the old town center became the hub for Jewish life, right next to city hall. Some walls of the city council building needed the adjacent Jewish houses for architectural support.

As was common in Christian society, Jews were subjected to special legislation. They were protected only if they paid special taxes and fees, kept to their small territory and were distinguishable by special hats and other items of clothing. At the same time, their success in enterprise and scholarship benefitted the city enormously. In many instances, their well-being depended on the mood of the local princes, in the case of Cologne the local Archbishop. Periods of relative peace and quiet could be dramatically ended by murderous pogroms. The religious fervor of the Christian crusades left an imprint on Cologne as well. In 1096, crusaders raided the Jewish quarter and killed most the town’s Jews. The community recovered, and subsequent archbishops proved more successful in protecting the Jews from the next bunch of crusading marauders.

In 1266, Archbishop Engelbert von Falkenburg issued a special privilege to protect Jews. Fascinatingly, the massive stone plaque has been preserved inside the Cologne Cathedral. He reaffirmed his right to regulate all issues relating to Jews under his jurisdiction. The Archbishop also promised to reinstate ancient rights to the Jewish community, such as the right to bury their dead in the Jewish cemetery and the right to continue their economic activity. Visitors need to seek out this impressive slab as there are no markers inside the church. It measures over two meters in height and reminded Christians of the special protection the Jewish community enjoyed, apparently very necessary at the time.

But at the end of the 14th century, the plague sparked yet another round of persecutions. In August of 1349, Cologne’s Christians set fire to the Jewish district, killed the inhabitants, destroyed the synagogue and distributed the property of the victims amongst themselves. This was not enough to end Jewish life in town. Indeed, records indicate repeated conflicts between city council and archbishops about the spoils: collecting fees and ‘protection money’ remained a lucrative business. In the dynamic relationship between church and city, the Jews became a political football.

Hatred and Envy

As one of the first cities of the Holy Roman Empire, Cologne expelled its Jewish community formally in 1424. By this time, Christian merchants had become prosperous. Commercial activities and banking had ceased to be sinful, or at least the church turned a blind eye. Power and confidence shifted to the city’s ruling elite, and they used their power to turn on the Jewish competitors. For many centuries, Cologne city laws prohibited the settlement of Jews – until 1798, when the French occupied the city and brought emancipation.

Today, the medieval Jewish quarter is the subject of archeological research. Right in the city center, plans for a Jewish museum are underway. The city’s coffers are notoriously empty but eventually, the Jewish museum will see the light of day. It will be a major step for demonstrating the city’s Jewish heritage to a larger audience. Once it is finished, it will become a focal point for understanding the complicated Christian-Jewish relations in the Rhineland region.

The excavations have unearthed religious structures like a synagogue and a mikvah. The experts also found many household objects including coins and jewelry. Scholars estimate that at the height of the community, around 800 people or about two per cent of the city’s entire population, lived in the Jewish quarter. Some experts even claim to have discovered the only ancient synagogue north of the Alps. The main synagogue served the community for centuries. After 1424, it was converted into a Christian chapel which was used as the city council hall of prayer until it was destroyed in the Allied bombings. Interestingly, when workers removed the rubble from the area around city hall, two fully intact gravestones from medieval times turned up: Sara – died in 1302 – and Rachel – died in 1323 – are now among the city’s oldest known Jewish inhabitants.

The Cologne Cathedral is also an interesting venue to study the prejudices of Christians. Along the outside of the venerated shrine of the Three Kings, Jews are depicted as caricatures with pointed hats and an ugly face. Inside the choir, carvings depict the ritual murder legend and a ‘Jewish sow’. Interestingly, no commentary or plaque explains these Anti-Semitic depictions. Most visitors of the ‘Dom’ will exit the church without any idea of them. They will also walk past the gargoyle depicting a ‘Jewish sow’, commemorating the nasty Anti-Judaism of the Catholic Church.

Jewish Traces in the Cathedral

Curiously, the emancipation of Jews led to a dramatic imprint of the community, even on the Catholic Church. As the ‘Dom’ was left unfinished for centuries, the completion became a national undertaking, famously led by the (Lutheran) Prussian monarchs who became German Emperors. Money from the entire Reich flowed to continue the and finish the cathedral. It was eventually completed in 1880. By this time, Jews had long resettled in Cologne and had rapidly become a mainstay of the successful bourgeoisie. The Oppenheim family actively participated in the efforts and financed dozens of stained glass windows. As was common for prominent patrons, their name can be found inscribed on the bottom of the windows. The Cologne Cathedral therefore displays all the contradictions of remembering and forgetting the past in one building. Furthermore, it showcases these cleavages underneath a façade of magnificent splendor and awe-inspiring architecture. Scratching at the surface will uncover dark chapters. But efforts continue to honestly face the demons of the past.